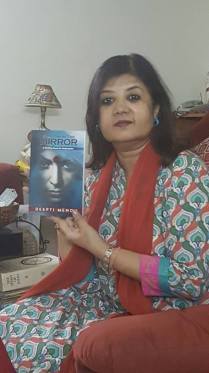

Deepti Menon is a well-known name among writers’ circles in India. Writing runs in her blood, as does teaching. She has lived in the Army as a child, and then as a wife, and travelled around the country to places, both beautiful and challenging. In 2002, Arms and the Women, her light-hearted book on life, as seen through the eyes of an Army wife, was published by Rupa Publishers, Delhi.

Many of her short stories have seen the light of day in anthologies as

varied as 21 Tales to Tell, Upper Cut, Chronicles of Urban Nomads, Mango

Chutney, Crossed and Knotted, Rudraksha, Love—an Anthology, The Second Life

and A Little Chorus of Love.

Today, Deepti Menon has agreed to give me an interview for my blog. We’ll talk about many a things, though our focus will be on satire as Mock, Stalk and Quarell, Readomania’s recent offering on satire in form of an anthology has been published and is available in online and offline stores all over India.

AN: How are you doing? Are you ready?

DM: Hi, Anirban! I am like that famed battery… Eveready!

AN: Ha ha! Good. Our focus of this interview will be on mainly satire. Satire, as we know, is difficult to master. It is a fine art. Can you tell us what inspired you to write a satirical tale? What makes writing satire so difficult?

DM: Writing satire is like tightrope walking. You can either walk on it, perfectly balanced, like a professional artiste, or you can make a perfect clown of yourself as you tumble over in a heap. Satire is a fine-tuned instrument, the kind of writing that needs to hit the target that it is aimed at. If you miss it, you end up sounding ludicrous or hyperbolic.

AN: We have seen recently the bold steps taken by the government, and we are also witnessing the social and political changes India is going through. Many have different opinions about these issues and events. What do you think of the role of satire in expressing one’s opinion in present time?

DM: 2016 will certainly go down as a red-letter year for many reasons – money matters, (pun intended), the Trump card and of course, the end of the Amma era in Tamil Nadu. Is it a coincidence that Cho Ramaswamy, noted humorist and political satirist, also passed away soon after?

Right from ancient times, satire was always seen as a weapon to hold up the ills of society. It is no different today as well. If two pieces are written on the same subject, one in prosaic language and the other veiled in satire, it is always the second one that will evoke more curiosity, and drive the point home, in my opinion.

AN: In the current Indian literary scene, we see a significant lack of satirical work. What is your response to such a situation?

DM: Very true, Anirban! The reason lies within ourselves. We, the homo sapiens, have turned into a dour, humourless society, unable to take a joke in the right spirit, be it in the case of cartoons, books, movies, newspaper articles or even WhatsApp messages. The powers above scream, like the proverbial Queen of Hearts in ‘Alice in Wonderland’, “Off with their heads!” And out pop the bans, which ironically, work well for those banned as they bring up the curiosity quotient.

Isaac Hayes couldn’t have put it more aptly when he said, “There is a place in this world for satire, but there is a time when satire ends and intolerance and bigotry towards religious beliefs of others begins.”

AN: In your story in Mock, Stalk and Quarrel titled, The Little Princess, we see a girl in search of true love, defying the social norms. Though, on closer look, it seems more like a parody. Through a mere matter of groom-matching, you have brought out the political situations of the country in a subtly humorous way. Tell us how you have come up with the idea of this story.

DM: Frankly, Anirban, this was a harmless little story that I had written a decade ago, because I wanted to come out with something light-hearted. It did not have any political allusions at all. When the idea of an anthology on satire came about, I stuck to the same story, but added on the rest, so that my story would fit the bill.

AN: Apart from situational comedy, we find many funny Wodehousian dialogues like:

“So what do you think? Isn’t he handsome?” Her eyes twinkled as she smiled at her daughter.

“Hardly, Mamma! He can get lost in a crowd of two!” The girl’s answer ruffled her mother’s feathers.

I have also read an article on Wodehouse by you. How has Wodehouse influenced you in your writing?

DM: I adore Wodehouse, and so, I love this question. I think his books are the epitome of good humour wrapped around in a writing style that is unique. I would often sit and chuckle over certain portions, even when I was travelling, and earned many strange looks in the process! I also feel that humour is one of the most difficult genres to master, and he is a master, indeed. I have friends who disagree with me on this point, but each to their own.

AN: At the end, the man with whom the girl falls in love identifies himself as ‘the Common Man’. In context of love and politics, its significance is something interesting to note down. Do you think that both a lover and a leader can be found amid the Common Man?

DM: “I think comedy and satire are a very important part of democracy, and it’s important we are able to laugh at the idiosyncrasies or the follies or vanities of people in power.” So said Rory Bremner.

I think in an ideal democracy, it should be the Common Man who rules. After all, it he who votes and brings people to power. So, a lover and a leader can be found in the Common Man. Please note that I am not alluding to the present Common Man, high on cough syrup, who sports a scarf.

AN: Recently, you have published your new novel Shadow in the Mirror under Readomania. Many congratulations to you for this success. What difference did you find between writing a short-story and a full-fledged novel? Of course, apart from short stories are short. Ha ha!

DM: Ha ha, indeed! J Thank you so much, Anirban. I feel that short stories need more skill, and that’s purely my opinion, because an entire story with a beginning, a middle and an end, needs to be encapsulated within a given word limit. Hence, the writing needs to be brief, and yet, sparkle enough to catch the imagination of the reader. A novel is a longer read, and the author has time to meander through the theme and make it work at a more leisurely pace.

AN: I have read your stories in Defiant Dreams, Urban Nomads and When They Spoke. A recurring theme of women empowerment can be noticed in your stories. This is also true for the story in Mock, Stalk and Quarrel too. There has not been a better time when the topic of women empowerment is of such importance. What do you think, as a writer, of the role of women in modern creative writing in India?

DM: My stories write themselves. I have never deliberately written a story on women’s empowerment. However, the issue is, perhaps, so strongly engrained in my psyche, that it comes out as a subconscious narrative. I think that all writers, men and women, should try and bring in a renaissance of gender equality and the empowerment of women and children.

AN: Does your new novel touch on similar issues?

DM: ‘Shadow in the Mirror’ is a work of fiction that has autobiographical elements in it. Thus, one of my main characters, who is a journalist, does fight against various issues that impact women negatively.

AN: What do you think of the current Indian literary scene? Also about the publishing trends?

DM: The current Indian literary scene is bursting at its seams with new writers being born and published every day. Today, everyone can write, and does, sometimes well, and at other times, with disastrous results. But I do think that it is a very positive trend which will throw up “full many a gem of purest ray serene” that would otherwise remain hidden “in the dark unfathomed caves of (the) ocean”.

Publishers have also mushroomed over the years. Today you have traditional publishers, vanity publishers and self-publishing, as well. Hence, it is easier to get your manuscript published than it was in the past, like back in 2002, when my first book, ‘Arms and the Woman’ (Rupa Publishers, Delhi) got published.

AN: Name a few of your favourite authors.

DM: George Eliot, Alexander Dumas for their classics, Somerset Maugham, O Henry, Guy de Maupassant and Jeffrey Archer for their short stories, and Agatha Christie and Conan Doyle for their mysteries, are among my favourites. I also enjoy Indian writers like RK Narayan, Ruskin Bond, Shashi Tharoor, Chitra Divakaruni Banerjee and Jaisree Mishra. I have also enjoyed all the books I have read from the Readomania collection.

AN: As an experienced writer, your advice to young writers?

DM: Love books, read and savour them, and identify the genre with which you want to be associated. Most importantly, enjoy what you write, for if you don’t like your own writing, no one else will either.

AN: Thank you for this interview. It’s been a pleasure.

DM: Thank you so much, Anirban, for the interesting questions. All the best with all your writing, and God bless!

AN: Thank you very much. Same to you.

But I have seen in many cases, the recipient gets so inflated that he refuses to work hard anymore. Remember, every work will require equal and preferably more effort than you have put in your previous work. So boost your confidence with positive criticism but don’t become overconfident. If you become overconfident, points in italic in following will happen.

But I have seen in many cases, the recipient gets so inflated that he refuses to work hard anymore. Remember, every work will require equal and preferably more effort than you have put in your previous work. So boost your confidence with positive criticism but don’t become overconfident. If you become overconfident, points in italic in following will happen.